Baroque Music takes its name from the Portuguese word for a “misshapen pearl.” The term was first used to describe an artistic style that seemed exaggerated and irregular compared to the balance and order pursued in Renaissance art. Yet this very sense of irregularity and splendor became the core of the Baroque aesthetic. Music, too, came to embrace dramatic contrasts and richly layered expression.

In Baroque Music, sound was no longer a simple succession of lines or harmonies. Clear major–minor tonality became the foundation of composition, and the new principle of basso continuo supported and unified the musical texture. New genres such as opera, concerto, and cantata were born, and music expanded beyond church and court into theatres, public halls, and the life of the city.

1. The Musical Language of Baroque Music

(1) The Establishment of Major and Minor

In the Renaissance, melody was largely shaped by the church modes, a system of ancient scales. In Baroque Music, these modes gradually gave way to the system of major and minor keys, a change that created a new, stable framework for composition. Over time, this major–minor system became the basic order that would govern Western music for the next few centuries. Major keys came to be associated with brightness, strength, and clarity, while minor keys suggested darkness, tragedy, or inward reflection. Baroque Music used these key-centred colours to draw emotional boundaries more clearly than before.

(2) Basso Continuo – A New Way of Accompanying

Perhaps the most decisive innovation of Baroque Music was basso continuo. In this practice, a sustained bass line forms the foundation of the entire piece, played by a keyboard instrument (harpsichord or organ) together with a low string instrument (cello or violone). The keyboard player did more than simply double the bass. Using numerical figures written above the bass notes, they improvised the harmonies in real time, filling out chords and guiding the flow of the music. In this sense, the continuo player functioned almost like a conductor at the keyboard, shaping balance, tension, and direction from within the ensemble.

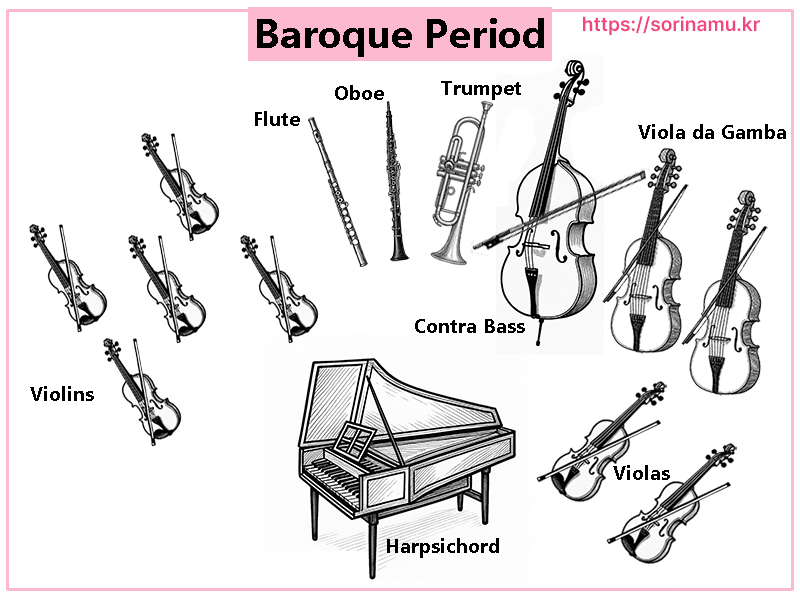

Baroque orchestra instrumentation: harpsichord and continuo bass supported the harmonic foundation, and the violin family formed the core. As the viola da gamba gradually disappeared, woodwinds such as the oboe, and brass instruments like the trumpet, added new colors to the ensemble.

(3) Ornamental Lines and Improvisation

Baroque Music is rich in ornamentation. Short trills, rapid arpeggios, and freely spun passagework appear frequently in both vocal and instrumental music. These ornaments were not mere decoration added on top of a finished work. They were a crucial way for performers to reveal their individuality and interpretive imagination. Composers often wrote only a relatively plain outline in the score. On stage, singers and instrumentalists were expected to add their own flourishes, turning a simple line into something dazzling and alive. In Baroque Music, the boundary between composition and improvisation was therefore much more fluid than in later periods.

(4) Contrast and Dramatic Expression

Another hallmark of Baroque Music is its love of contrast. Strong and soft dynamics, solo voice and full chorus, soloist and ensemble, high and low registers – these oppositions collide and interweave to create drama. In vast church spaces and resonant courts, such contrasts gave sacred works an almost theatrical intensity. On the opera stage, they heightened the tension of the story, allowing music to move between whispered intimacy and overwhelming fullness, like a drama painted in sound.

(5) The Doctrine of Affections – Sustaining a Single Mood

Many Baroque composers preferred to sustain one dominant emotion throughout a movement rather than mix several different moods. This approach is often called the Doctrine of Affections. Each piece was designed to express a specific affection – joy, sorrow, anger, peace – as purely and consistently as possible. In German-speaking lands, this idea was closely tied to the Lutheran chorale. Simple congregational hymns provided clear, memorable melodies that could shape the emotional character of an entire cantata or organ prelude. In Baroque Music, a familiar chorale tune might become the structural pillar of a large work, guiding its mood from beginning to end.

2. Major Genres – The Birth of New Forms in Baroque Music

(1) Opera – A New Art Form on Stage

The most innovative genre to emerge in early Baroque Music was opera. Around 1600, in Florence, humanist poets and musicians began experimenting with ways to revive the spirit of ancient Greek drama, bringing together music, poetry, and stagecraft. At first these works were simple and often based on mythological stories, but they rapidly grew in complexity. With Claudio Monteverdi’s “L’Orfeo” (1607), opera achieved a new level of musical and dramatic refinement. Solo arias, choruses, and instrumental interludes intertwined to build tension and release, and opera soon became a central entertainment in courts and urban theatres across Europe.

(2) Oratorio and Cantata

As opera blossomed in secular theatres, the oratorio developed as its sacred counterpart. Oratorios told biblical stories using soloists, chorus, and orchestra, but without scenery or acting. In the hands of George Frideric Handel, the oratorio reached its peak in works such as “Messiah”, where narrative, meditation, and communal praise unfold on a grand scale.

The cantata was usually more compact than an oratorio. In the Lutheran tradition, cantatas often followed the church year, setting scriptural texts or hymn stanzas for specific Sundays and feast days. Johann Sebastian Bach’s many church cantatas masterfully integrate chorales, solo arias, recitatives, and instrumental sections, forming the backbone of Lutheran worship in his time.

(2-1) Chorale – From Luther’s Melody to Bach’s Art

After the Reformation, Martin Luther introduced simple hymns that ordinary worshippers could sing together. These chorales, sung in German rather than Latin, became the musical voice of the faith community.

By the time of Baroque Music, chorales had grown far beyond their origins as congregational songs. Bach, in particular, transformed them into rich artistic structures. He harmonized chorale melodies in four-part choir settings, expanded them into organ preludes, and embedded them as opening and closing movements in cantatas. In his works, a familiar chorale often functions as the central pillar of the entire piece. What began as a straightforward confession of faith becomes, in Bach’s hands, a monumental choral architecture where theology and musical craft converge.

(3) Concerto and Sonata

In instrumental Baroque Music, the two most important forms were the concerto and the sonata.

The concerto is built on dialogue between a solo instrument (or group of soloists) and the full ensemble. Antonio Vivaldi was a central figure in shaping this genre. He helped define the ritornello form, in which a recurring orchestral section alternates with freer solo episodes. This model became the blueprint for many later concertos, including those of the Classical era.

The sonata flourished especially in chamber settings. Trio sonatas for two upper instruments and basso continuo were common, as were solo sonatas for one instrument with continuo. Through these intimate forms, composers explored the singing quality of instruments and the expressive possibilities of Baroque Music on a more personal scale.

(4) Suite and Fugue

The suite developed by grouping together stylized dances. Movements such as allemande, courante, sarabande, and gigue are typically arranged in a regular order, each with its own tempo and character. Suites were played both at court and in private homes, on instruments ranging from lute and harpsichord to full ensembles.

The fugue is a highly contrapuntal form in which a single theme (the subject) is successively imitated and developed in several voices. As Baroque Music matured, the fugue became the supreme test of a composer’s mastery of counterpoint. In Bach’s hands, the fugue reached an unparalleled level of structural clarity and intellectual depth.

3. The Development of Instruments and Instrument Making

Image Sources

All instrument images referenced in this section are based on public domain or open-access materials from museums and libraries.

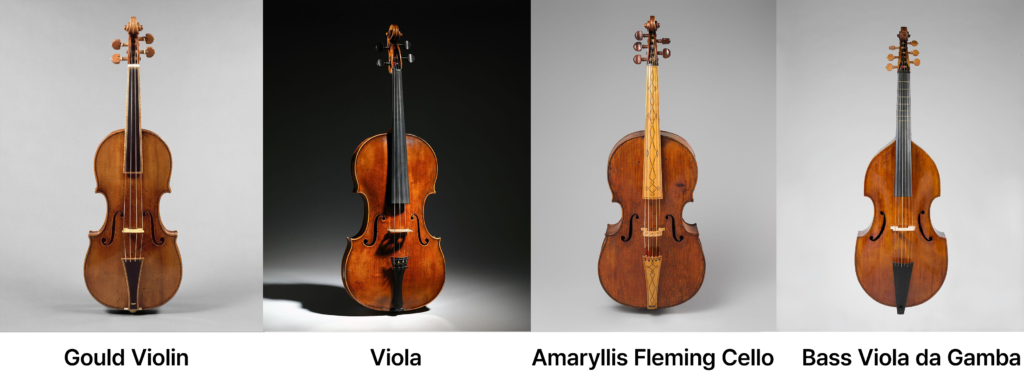

String Instruments

Violin “Gould” – made by Antonio Stradivari in 1693 in Cremona, Italy. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Object No. 55.86a–c)

Viola – made by Jacob Stainer around 1660 in Innsbruck, Austria. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Object No. 2013.910)

Baroque Violoncello “Amaryllis Fleming” – made by the Brothers Amati around 1610 in Cremona, Italy. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Object No. 2023.331)

Bass Viola da gamba – made by John Rose around 1580 in London, England. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Object No. 1989.44)

Woodwinds

Flute – made by Garion around 1720–40 in Paris, France. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Object No. 2005.365)

Oboe in C – made by Jacob Denner around 1735 in Nuremberg, Germany. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Object No. 89.4.1566)

Bassoon – made by Wolfgang Thomae around 1750 in Leipzig, Germany. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Object No. 2003.345)

Brass

Natural Trumpet – made by Johann Wilhelm Haas around 1680 in Nuremberg, Germany. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Object No. 54.32.1)

Natural Horn – made by Jacob Schmidt around 1710–20 in Frankfurt, Germany. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Object No. 14.25.1623)

Keyboards

Harpsichord – made in late 17th-century Florence, Italy. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Object No. 45.41a–c)

Silbermann Organ – installed in Georgenkirche, Rötha, Germany, in 1721 by Gottfried Silbermann. Photo by Soralein (2015) / Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Chamber Organ – decorated by Franz Caspar Hofer around 1750 in Germany. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Object No. 89.4.3516)

Trost Organ – installed around 1730 in the town church of Waltershausen, Germany, by the Trost family. Still used today and featured in recordings of Bach’s organ works.

Percussion

Kettledrum (Timpani) – made in late 18th-century Bavaria, Germany, from bronze, iron, and animal skin. Represents the form of timpani used in late Baroque and early Classical orchestras. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Object No. 1991.137.2a, b)

(1) The Golden Age of Strings – The Violin Family and the Lute

In the Renaissance, the vielle was a key ancestor of modern bowed string instruments. From it, two main lines evolved: instruments held on the arm and instruments held between the legs.

The viola da braccio (“viol of the arm”) was played on the shoulder and tuned in fifths. Its clear, high register and agile response made it ideal for melodic lines. The modern violin, viola, and cello all descend from this family.

As Baroque Music developed, the violin family moved to the centre of musical life. The violin carried bright, penetrating melodies; the viola filled the middle register, balancing the texture; and the cello provided firm bass support.

Although the cello is held between the knees and can easily be confused with the viola da gamba, it actually belongs to the violin family. It is tuned in fifths like the violin and viola and has a clearer, more projecting tone than instruments of the gamba family. Early Baroque cellos often had five strings, extending their range and allowing both deep bass and singing upper lines, which made them essential in both ensemble and solo Baroque Music.

The finest instruments of the violin family were crafted in Cremona by makers such as Stradivari, Guarneri, and Amati. Their instruments are still regarded as masterpieces today, symbolizing the precision and expressive richness of Baroque Music.

By contrast, the viola da gamba (“viol of the leg”) was tuned mostly in fourths and produced a softer, more veiled tone. It played an important role in earlier chamber music, but as Baroque orchestras grew in size and power, the gamba family gradually declined. Eventually, the double bass, with its greater volume, took over the low-string role in larger ensembles.

Image source: Caravaggio, “The Lute Player,” c. 1595–96, Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia – Public Domain.

The lute remained a beloved instrument in the early Baroque period. Its delicate and warm sound made it a favourite in household music-making and courtly gatherings. Bach even wrote independent suites for lute, treating it as a fully fledged solo instrument. Over time, however, the louder violin family and the harpsichord took centre stage in public venues, and the lute slowly withdrew from the main stage.

(2) The Settling of Woodwinds – Flute, Oboe and Bassoon

With the rise of Baroque Music, woodwind instruments underwent important changes. The recorder, which had been widely used in the Renaissance, gradually gave way on stage to the transverse flute. Made of wood and equipped with relatively simple finger holes and a few keys, the Baroque flute had a gentle, mellow sound. Its intonation was delicate to control, but precisely for that reason it could colour solo and ensemble music with subtle shading.

The oboe was one of the first new woodwinds to establish itself firmly in Baroque Music. Its bright yet flexible tone made it suitable for solo lines, chamber music, and leading voices in the orchestra. Bach and Handel frequently used the oboe as a primary vehicle of expression, especially in sacred works and concertos, where its singing quality could convey both joy and sorrow.

The bassoon occupied the lower register, supporting the continuo bass line. Its warm, dark tone anchored the harmony and helped balance the ensemble. At times it also stepped forward with independent melodic lines, revealing a surprisingly lyrical side. Though simpler in construction than the modern bassoon, the Baroque instrument gave the lower part of the orchestra a stable, resonant foundation.

Together, the flute, oboe, and bassoon gave Baroque Music a richly coloured wind palette. Each instrument retained a distinctive voice, yet their blend contributed to the subtle interplay of contrast and unity that defines Baroque orchestral sound.

(3) The Use of Brass – Natural Trumpet and Natural Horn

In the time of Baroque Music, brass instruments were still natural instruments without valves. The trumpet and horn could only play notes from the natural harmonic series determined by the length of their tubing, which limited their available pitches. Even so, composers and players used these constraints to shape a brilliant and powerful sound.

The natural trumpet flourished in courts and churches, where it announced royal entries, military victories, and grand liturgical celebrations. Its clear, shining tone was perfect for expressing majesty and solemnity. In the works of Bach and Handel, trumpets often join choirs and organs to crown climactic passages with blazing sonorities.

The natural horn, originally a hunting signal instrument, gradually entered the musical life of the court. Its coiled shape and wide bell produced a round, mellow tone that bridged the gap between woodwinds and strings. Skilled players used their lips and subtle hand movements inside the bell to adjust pitch, turning a simple hunting horn into a flexible orchestral instrument.

(4) Keyboards at the Centre – Harpsichord and Organ

In Baroque Music, keyboard instruments stood at the very centre of musical practice, especially through their role in basso continuo.

The harpsichord (called cembalo in German and clavecin in French) produces sound by plucking the strings when keys are pressed. It served both as a solo instrument and as the harmonic engine of the ensemble. In continuo playing, the harpsichordist realised chords, filled in inner lines, and animated the texture with ornaments and running figures. Bach’s Italian Concerto is a prime example of how the harpsichord can suggest orchestral contrasts with nothing more than a single keyboard.

The organ filled church interiors with massive waves of sound. With its many ranks of pipes and stops, it could move from intimate prayer to overwhelming splendour. For composers, the organ was a laboratory for exploring counterpoint, tonality, and large-scale form.

Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor is perhaps the most famous embodiment of the dramatic side of Baroque organ music.

The Trost Organ itself, built around 1730, is an important witness to central German organ building. Each stop has a distinct colour, and the blend of manuals and pedal creates a living architecture of sound.

Even today, the piece is performed using techniques that closely reconstruct the original manner of playing. Each note reveals subtle differences of color, and the warm resonance unique to an 18th-century organ can be felt thanks to the gentle natural acoustics of the space.

Preview of the Performance Scene

These images show the actual performance of the piece above. The organist moves between several manuals with both hands while using the pedalboard with the feet to play the bass line. Keys and pipes breathe together like a single living body, bringing back, in the present, the sound that once filled Baroque church interiors.

Smaller chamber organs were used in homes and small chapels. With fewer pipes but a clear, gentle tone, they were well suited to solo pieces and song accompaniment. People of the Baroque era cherished not only the grandeur of large church organs but also the quiet, room-filling presence of these more intimate instruments.

(5) The Emergence of Timpani

Until the late Renaissance, percussion instruments were used mainly in military and ceremonial contexts. Kettledrums (often called nakers) were mounted on horseback to signal commands or mark marching rhythms, serving practical rather than expressive purposes.

In Baroque Music, kettledrums evolved into fully tuned timpani. Adjustable tension mechanisms allowed players to set specific pitches, and two or more drums were used together as a pair or set. From this point on, timpani became a standard part of the orchestra.

Timpani often joined trumpets in festive court music and sacred celebrations, reinforcing cadences and structural pillars with their deep, resonant strokes. The bowls were usually made of copper, with animal skin stretched over the top. Tuning changes were slower than on modern instruments, but skilled players could still shape subtle rhythmic and tonal nuances.

In the sacred works of Bach and the oratorios of Handel, the combination of trumpets and timpani became a sonic symbol of royal power and heavenly glory. That combination represents one of the most striking sound images of Baroque Music.

4. Major Composers and Works

Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643)

“The pioneer who opened the age of opera in the Baroque era”

Nationality: Italian

Activity: Court musician in Mantua; maestro di cappella at St Mark’s Basilica, Venice

Main genres: Madrigals, opera, sacred music

Achievement: Monteverdi stood on the late Renaissance madrigal tradition and introduced new harmonies and expressive devices, turning music from simple decoration into a central language for telling stories and conveying emotion. By clearly separating and contrasting vocal and instrumental roles, he developed ways of expressing a character’s feelings and the tension of a scene in musical terms. His work L’Orfeo is regarded as the first fully accomplished opera and the starting point from which the genre took root.

In Venice he combined large-scale choral forces with orchestra to establish a basic model of Baroque stage music that embraced both church and theatre. These experiments spread beyond Italy to many European cities and became an important reference point for later composers writing opera and sacred music.

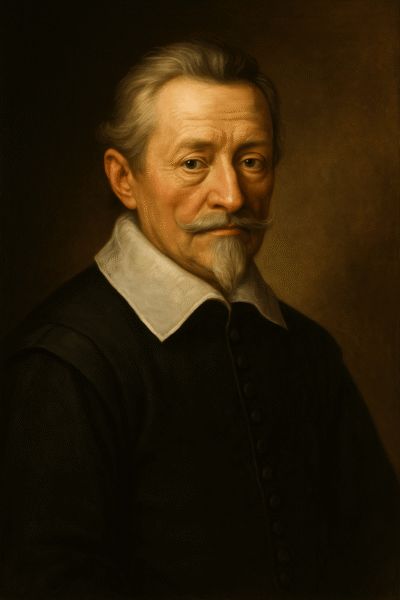

Heinrich Schütz (1585–1672)

“The pioneer who laid the foundations of German Baroque music”

Nationality: German

Activity: Kapellmeister at the Dresden court; composer of church music in various cities

Main genres: Sacred music, choral works, polyphonic motets

Achievement: Schütz is often called the father of German church music. In Venice he studied with Giovanni Gabrieli, learning the Italian sense of harmony and the techniques of polyphonic writing, and then applied them to German biblical texts and liturgical music, building a solid foundation for later Lutheran church music. His works focus on bringing out the meaning of scripture vividly in sound, and on expressing the emotions and spiritual depth of faith.

Schütz’s music is regarded as the high point of German music before Bach and exerted a powerful influence on all later German composers. His Passion settings and biblical motets played a key role in completing the Lutheran liturgical tradition and showed how language and emotion could be perfectly united in German music.

Dieterich Buxtehude (1637?–1707)

“The great master of North German organ music who deeply impressed Bach”

Nationality: German (probably born in Denmark)

Activity: Organist at St Mary’s Church, Lübeck

Main genres: Organ music, sacred cantatas

Achievement: Buxtehude was the composer who brought the North German organ tradition to completion, developing the forms of the organ prelude and fugue. His performances left a deep impression on musicians across Europe; the young Bach famously walked some 400 km to hear him play in person.

His works became an important turning point in the development of German church music and left clear traces in Bach’s organ pieces and chorale style. By helping to establish the form and structure of large-scale sacred works, Buxtehude offered an important model for later composers.

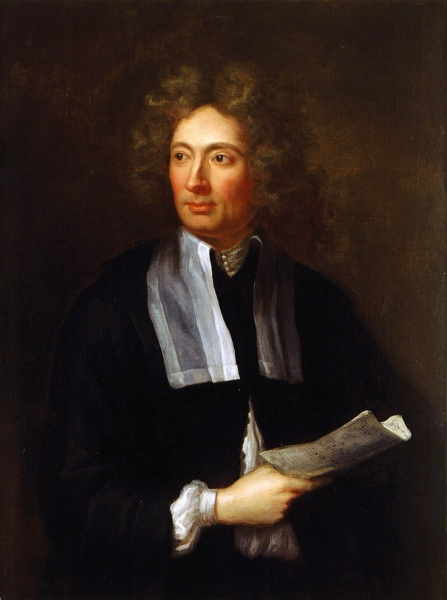

Arcangelo Corelli (1653–1713)

“The composer who codified the concerto grosso and opened the violin era”

Image source: Portrait of Arcangelo Corelli painted by Hugh Howard (1697). Provided by Wikimedia Commons.

Nationality: Italian

Activity: Active mainly in Rome in court and church music

Main genres: Concerto grosso, sonata

Achievement: Corelli organised the form of the concerto grosso and created a standard that later composers could follow. His music is characterised by smooth, singing melodies and a finely balanced sense of harmony, and it played a crucial role in establishing the violin as a leading instrument. As a central figure in Roman musical life, he exerted strong influence on many pupils and performers.

Corelli’s works inspired Vivaldi, Handel, and Bach and stand at the heart of Baroque musical development. In particular, his trio sonatas and concertos laid the groundwork for all later concerto writing, and as his music was performed across Europe, it helped usher in a new musical era.

Henry Purcell (1659–1695)

“The composer who opened the path for English opera and theatre music”

Image source: Portrait of Henry Purcell painted by John Closterman (1695). Provided by Wikimedia Commons.

Nationality: English

Activity: In charge of music for the royal chapel and for the theatre

Main genres: Opera, theatre music, sacred music

Achievement: Purcell completed the first full-scale English opera with Dido and Aeneas. He developed a way of setting the rhythm and emotion of speech so that they flow naturally into music, and as a leading figure in London’s theatre world he opened a new era for English music.

Although his life was short, Purcell established an independent English musical tradition and left a deep mark on later composers. His works remain the foundation of English vocal and theatre music to this day, and he is remembered as one of the composers English audiences love most.

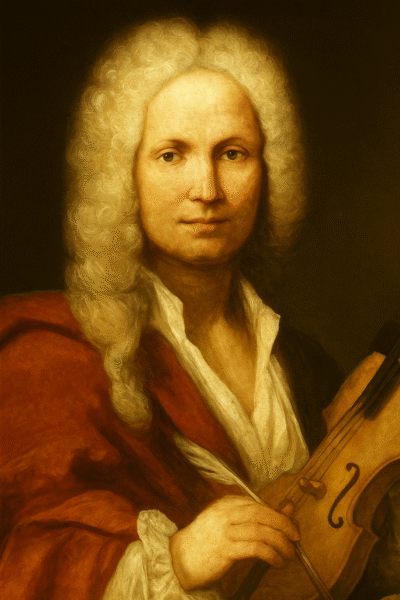

Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741)

“Master of the brilliant concerto, at the centre of Baroque instrumental music”

Nationality: Italian

Activity: Music director at the Ospedale della Pietà in Venice; opera composer

Main genres: Concertos, opera, sacred music

Achievement: Vivaldi established the concerto as a central genre of Baroque instrumental music. He wrote more than 500 concertos. His collection L’estro armonico (Op. 3, 1711) caused a sensation across Europe and clearly articulated ritornello form, defining the structure of alternation between soloist and ensemble. These works were widely performed, and Bach arranged several of them for keyboard in order to study them.

His later set Le quattro stagioni (The Four Seasons, 1725) vividly depicts the changing seasons in nature and human life and made Vivaldi’s name famous throughout the world. Its rich expressive writing and sharp contrasts of light and shade embody the spirit of the Baroque and have made it one of the most loved concerto collections today.

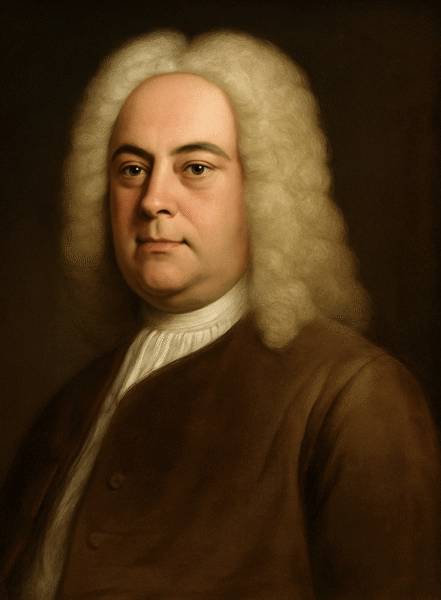

George Frideric Handel (1685–1759)

“A giant of opera and oratorio whose art blossomed in England”

Nationality: Born in Germany; later naturalised British

Activity: Worked in Hamburg and Italy; later settled in London

Main genres: Opera, oratorio, instrumental music

Achievement: Handel fused Italian opera with German and English traditions and established the oratorio, with chorus and orchestra at its centre, as an independent genre. In oratorios such as Messiah, he combined dramatic narrative with religious content and showed that music performed in concert form, without staging, could still be deeply moving.

He presented new works at royal ceremonies, city festivals, and charity concerts, helping to create a public musical culture that court and citizens could share. Handel’s music later played a major role in shaping English musical identity.

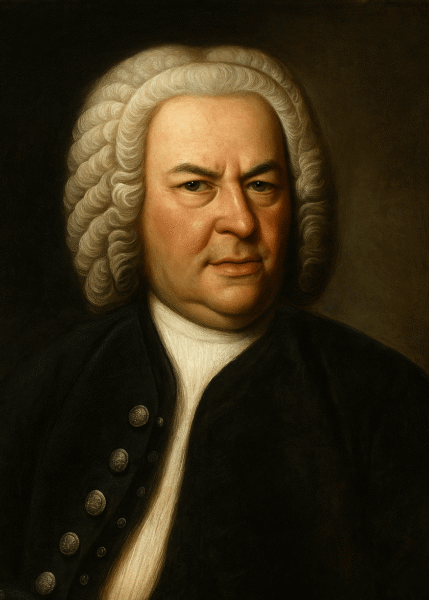

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750)

“The summit of counterpoint and the great synthesiser of Baroque music”

Nationality: German

Activity: Court organist in Weimar; Kapellmeister in Köthen; Thomaskantor in Leipzig

Main genres: Cantatas, Passions, organ works, concertos, suites, fugues

Achievement: Bach raised contrapuntal writing to its highest level and brought together the musical styles of many regions to create the summit of Baroque music. Works such as the Brandenburg Concertos, the St Matthew Passion, and the Mass in B minor are regarded as masterpieces of the highest order in every field of vocal and instrumental music.

Placing the Lutheran chorale at the centre of his sacred output, he built large-scale cantatas on melodies that the congregation could sing together. These chorale tunes became pillars supporting both the emotion and the message of faith in his works and showed how music could become a language of belief.

Through The Well-Tempered Clavier he demonstrated the practicality and potential of all 24 major and minor keys, bringing about a major shift in how Western music was composed and taught. The collection laid the foundation for modern tonal music and became an indispensable textbook for composers from Mozart and Beethoven to Chopin. Although he was not greatly celebrated in his lifetime, he is now honoured as the “father of music” and a standard against which Western music is measured.

Conclusion

The era of Baroque Music established the major–minor tonal system and introduced basso continuo as a new foundation for musical structure. Genres such as opera and oratorio, concerto and sonata were born, carrying music beyond church and court into theatres and public life.

The development of strings, winds, brass, and keyboards laid the foundations of the modern orchestra. Composers like Monteverdi, Schütz, Vivaldi, Handel, and Bach explored every corner of vocal and instrumental writing, in both sacred and secular realms, and showed how far Baroque Music could reach in depth and variety.

The splendour, dramatic contrasts, and sustained emotional focus of Baroque Music paved the way for the Classical period that followed. What was once dismissed as a “misshapen pearl” ultimately proved to be one of the brightest jewels in the history of Western music.

Further Reading

Western Music History ① Ancient Greek Music and Roman Traditions (600 BC – AD 400)

Western Music History ② Medieval Music (500–1400)

Western Music History ③ Renaissance Music (1400–1600)

Western Music History ③ Renaissance Music (1400–1600) | The Music of Human Emotion